The Konbit Bibliyotek Project

Background

Cite Soleil is a municipality that lies on the northwestern edge of Port au Prince, Haiti’s capital city. As mentioned above, it is known as Haiti’s largest ghetto. Cite Soleil has experienced a vicious cycle of political and gang violence, which leads to economic and social marginalization, which in turn creates the conditions for more violence. The stigma associated with Cite Soleil is significant, which not only reinforces the social isolation of the community, but has been internalized by many of its young people who see that society only expects them to grow up to be criminals.

However, the vast majority of people living in Cite Soleil are ordinary people trying to make an honest life for themselves and their families. Cite Soleil is full of young people with talent, potential, and dreams of a better future. Over the past six years, a social movement named Konbit Soley Leve has dedicated itself to identifying, strengthening, and highlighting all that is positive about Cite Soleil, and working to change the image that the world as of this community. In the past year and a half, there has actually been a truce between the major gangs of Cite Soleil, leading to an unprecedented period of peace that the community would like to build on.

The Library Story

In early 2017, a group of young artists and intellectuals in Cite Soleil decided that it was important to build a library in Cite Soleil. Over the past decade, there had been a lot of investment in youth spaces, but these spaces were mostly for sports. They brought the idea to Konbit Soley Leve, who advised them that instead of writing a proposal to a donor, they should first look for support in their own community. They should give ordinary people in Cite Soleil the opportunity to participate in making this dream a reality, that they should be the first donors. So Konbit Soley Leve and the youth group began to go door to door with a cardboard box, asking for contributions.

In early 2017, a group of young artists and intellectuals in Cite Soleil decided that it was important to build a library in Cite Soleil. Over the past decade, there had been a lot of investment in youth spaces, but these spaces were mostly for sports. They brought the idea to Konbit Soley Leve, who advised them that instead of writing a proposal to a donor, they should first look for support in their own community. They should give ordinary people in Cite Soleil the opportunity to participate in making this dream a reality, that they should be the first donors. So Konbit Soley Leve and the youth group began to go door to door with a cardboard box, asking for contributions.

For the sake of transparency, each time someone contributes, the donor would take a

The campaign went viral. People across Cite Soleil, many living on less than $2 a day, began to donate, then across Port au Prince, then Haiti, then the world. Schoolchildren gave up their lunch money, strangers who overheard about the project on public transport asked to contribute. A volunteer once drove all the way from Port au Prince to Les Cayes (an eight-hour round trip) just to pick up a single gourde that a little boy wanted to contribute. The idea was to change the perception of who is a donor and who is a beneficiary, and give people a chance to participate in a community vision.

Progress to Date

After 25 weeks of fundraising, 3,123 individual donors have contributed 1,080,771 gourdes (approximately $12,432 USD), and 3,641 books.

After 25 weeks of fundraising, 3,123 individual donors have contributed 1,080,771 gourdes (approximately $12,432 USD), and 3,641 books.

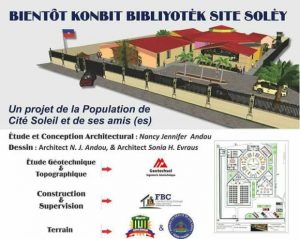

An architect from Cite Soleil has designed the plan of the library, which is a grand vision. It is important that the library be an impressive building because people in Cite Soleil are tired of being treated as second-class citizens – they believe they deserve a first-class library. The library may cost as much as 10 times as much as has been raised so far – but given the remarkable success to date and how much the community believes in this vision, there is confidence that the library will be built.

Help has come in many forms. The local authorities in Cite Soleil have already dedicated a space for the library in Place Fierte – the public park in the heart of Cite Soleil. Young Haitians have volunteered to provide graphic design and marketing services, to produce promotional songs and videos. A company performed the land survey for free (which would have otherwise cost $7000), and a construction company has volunteered to build the library without payment. There are already commitments for, once the library is built, furniture, free internet, and language classes. There are groups that have volunteered to train young librarians for free.

This project is called Konbit Bibliyotek for a reason, because it leverages the principles behind the traditional Haitian practice of Konbit: if everyone contributes what they can, we can collectively achieve what no one could achieve alone. The community has already done so much and gone so far – and it is now looking for more friends and allies to join in, and help turn this dream into a reality.

The Impact

If this dream is realized, it will mean many things. First, it will provide an accessible space to promote learning, research, and debate in the heart of Cite Soleil; this will become a new center to provide community services. Second, it will help to change the image of Cite Soleil, both to young people in the community and to the rest of the world. Third, it will provide a new model of community-driven development and a statement of how Haitians can lead the way to a different future.

If this dream is realized, it will mean many things. First, it will provide an accessible space to promote learning, research, and debate in the heart of Cite Soleil; this will become a new center to provide community services. Second, it will help to change the image of Cite Soleil, both to young people in the community and to the rest of the world. Third, it will provide a new model of community-driven development and a statement of how Haitians can lead the way to a different future.How You Can Help:

• If you are in Haiti, contact Robillard.louino@gmail.com to arrange a visit to the library site, or to arrange dropping off books or making a donation.

• If you are outside of Haiti, you can contribute through our Global Giving site: https://www.globalgiving.org/projects/konbitbibliyotek/#me

• If you have any expertise, connections, or services to offer in support of this vision, contact Robillard.louino@gmail.com

_________________________________________________

Louino Robillard is a Haitian community leader who was raised in Cite Soleil, Haiti’s largest ghetto. He has co-founded the Konbit Soley Leve movement, the Cite Soleil Peace Prize, and many other grassroots social change initiatives across Haiti. He graduated from the Future Generations Graduate School in 2013 with a Master’s in Applied Community Change and Peacebuilding.

Louino Robillard is a Haitian community leader who was raised in Cite Soleil, Haiti’s largest ghetto. He has co-founded the Konbit Soley Leve movement, the Cite Soleil Peace Prize, and many other grassroots social change initiatives across Haiti. He graduated from the Future Generations Graduate School in 2013 with a Master’s in Applied Community Change and Peacebuilding.

Future Generations University teams up with AmeriCorps West Virginia!

West Virginia ranks third in the Nation for producing AmeriCorps volunteers. Each year over 1,000 individuals serve as AmeriCorps members in the state. Many AmeriCorps volunteers serve in their hometowns, while others come from across the country to make West Virginia their home for the year. AmeriCorps members change lives through mentoring, respond to disasters -like the June 2016 flooding, increase access to healthy and local food, preserve historic properties, and many conservation activities working with state agencies and non-profit entities alike.

West Virginia ranks third in the Nation for producing AmeriCorps volunteers. Each year over 1,000 individuals serve as AmeriCorps members in the state. Many AmeriCorps volunteers serve in their hometowns, while others come from across the country to make West Virginia their home for the year. AmeriCorps members change lives through mentoring, respond to disasters -like the June 2016 flooding, increase access to healthy and local food, preserve historic properties, and many conservation activities working with state agencies and non-profit entities alike.

Read on for an overview of the program!

Term 4: Synthesis & Integration—Analyze results of Project-based Research in community from both summative and formative perspectives within ePortfolio. Students are challenged to incorporate lessons learned during their MA studies with experiential-based reflection on AmeriCorps service.

Maple Sap Collection and Syrup Processing in WV

|

| Sap dripping on a good run |

|

| Collecting sap at Principia College |

Maple Syrup in West Virginia? Doesn’t that stuff come from Vermont? Good question, and the answer is, well, yes. Ever since the marketing of “Vermont Maid”, an imitation maple syrup product, Vermont has been the state most closely associated with maple syrup. That being said, Quebec Canada is actually the largest producer of the sweet syrupy substance. And, Maine, New York, and Wisconsin are not far behind. What is less well known, is that West Virginia actually has more tappable sugar maple trees than Vermont, and a history of sugaring. All across the state there are place names like Sugar Grove, Sugar Creek and Sugar Valley, places with a history of making maple syrup. The last five years has seen resurgence in interest in “sugaring,” and the establishment of new sugar camps.

|

|

Main lines bringing sap to the sugarhouse

at the Dry Fork Maple Works |

|

| Typical environmental conditions in a sugarbush |

Future Generations is also working with the Department of Agriculture’s Veterans and Warriors in Agriculture Program to offer a certificate course titled “Maple Sap Collection and Syrup Production,” while designed to meet the needs of veterans, this course will be open to anyone wanting to get into the maple business.

|

| Whoever said that that 2.5% is the sweetest thing in a sap bucket? |

Bridging the Gap: Peace Development Between the Leprosy-Affected Community and Surrounding Community in Addis Ababa

|

|

Fisseha with community representatives from the leprosy-affected

community and non-leprosy-affected surrounding community

|

The concept of the project came about from my work with those with leprosy in affected communities. In many countries, people affected by leprosy face a number of social and economic problems, such as discrimination and stigma. These issues are even worse for individuals who experience disability due to leprosy. They are more vulnerable to the endless stigma and discrimination than any other form of disability in our society.

Even after someone with leprosy has been cured, they’re unable to lead an ordinary life due to the consequences of lingering complications. Some of the most difficult complications experienced are they forced to live as a colony in specific area and they did not get access for education. As a result of the wide misconceptions that exist about leprosy, many of those affected are forced to leave their birth places and live in segregated groups, known as leprosy colonies. In the capital of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, individuals who have been affected by leprosy are deliberately pushed out of the city and made to settle in a solid waste dumping site with no infrastructure and poor social services.

The leprosy-affected community of Addis Ababa is called the “Zenebework Community.” The majority of early settlers in the area were leprosy victims who largely migrated here from various other parts of the country– mainly Amhara, Tigray, Oromia, and SNNP regions. Their goal was to receive medical treatment for their leprosy at ALERT (All African Leprosy Rehabilitation and Training Centre) Hospital, formerly known as Zenebework Hospital.

After treatment, the leprosy victims were supposed to go back to their place of origin, as direct by the government, but the majority of them refused, preferring to remain in this area where they’d received treatment. This resulting settlement was named after the Zenebework Hospital, which had been established in 1932 and named after Princess Zenebework, daughter to Emperor Haileselassie. In 1949, the Abune Aregawi/Gebre Kristos Church was established in the same area, resulting in this name also being used for the locality. When construction began on the hospital in its present form as ALERT in 1967 and was later inaugurated in 1971, many other institutions, such as schools, followed. This provided a basic infrastructure that the leprosy victims had previously been completely without.

Below is an outline of the expected outcomes and major activities set in place to bring about this objective:

Expected Outcomes

Major Activities

Fisseha is an Ethiopian who has more than 15 years of proven and practical work experience in different organizations. He’s worked in agricultural research institutes and both international and local NGOs, while holding different positions such as Research Technical Assistant, Development Facilitator, Project Officer, Program Coordinator, and Executive Director. He currently runs an NGO called Child of Present a Man of Tomorrow (CPMT) in Ethiopia, which works to promote the wellbeing of women and children. He is also presently studying a Master’s degree in Applied Community Change in Conservation concentration at Future Generations University to complement his backgrounds in agriculture, development and leadership.

Fisseha is an Ethiopian who has more than 15 years of proven and practical work experience in different organizations. He’s worked in agricultural research institutes and both international and local NGOs, while holding different positions such as Research Technical Assistant, Development Facilitator, Project Officer, Program Coordinator, and Executive Director. He currently runs an NGO called Child of Present a Man of Tomorrow (CPMT) in Ethiopia, which works to promote the wellbeing of women and children. He is also presently studying a Master’s degree in Applied Community Change in Conservation concentration at Future Generations University to complement his backgrounds in agriculture, development and leadership.Musings of a Naturalist III: QUETZALS AND COSTA RICA

Jorge, a member of the extensive Serrano family, grew up in quetzal country and while studying rural tourism at his local high school, realized that showing quetzals to visitors could be a key income generating opportunity for the family – if only they could work out a system.

‘Quetzal tours’ were already in vogue in other quetzal hot spots such as Savegre Valley and Monteverde. Eager to see one of these birds, we visited the Savegre Valley where we engaged Marino Chacon as our driver/guide. Early one February morning he drove us slowly up the main road from the Savegre Lodge until he heard a bird and then quickly spotted a fine male sitting on a moss-covered branch in the cloud forest. There, in front of us, was an experience we will long remember: the classical image of a stunning quetzal.

In 2009 Jorge started his scheme by coaxing local farmers to search their property each morning, looking for quetzals, and should they find a bird, report to the lodge on their cell phones. Quetzals feed on wild fruit – especially wild avocados – as well as on frogs and lizards (during the rainy season) and once breakfast is ingested they usually sit quietly on a branch for extended periods. Thus guests at the lodge who are interested – and have paid a substantial fee – climb aboard a vehicle for a ride of fifteen or so minutes to the selected farm. Once you know where a bird is resting, the chances of arriving guests seeing a quetzal is high. Another seasonal method of locating quetzals, and one popular along main roads, is to find a nest with chicks and then watch the adult birds coming and going. The nesting season on the Pacific side of the Cerro del Muerte uplift normally begins early in March and lasts into May.

|

|

The lodge’s mission statement speaks to the importance

of taking pride in caring for Mother Nature for future generations.

|

Jorge’s program, started with only two farmers, but now has become so successful that his list of reporting individuals has grown to twenty-two with two more waiting in the wings. In the high season, the lodge runs three ‘quetzal tours’ a day, each with a limit of ~6 people per group. It is mportant to limit the number of visitors to any one site, Jorge says, so as not to overly disturb the birds. Evidence of the success of this program is that some farmers are now planting wild avocados and other fruit-bearing trees on their properties.

_________________________________________________________

|

Dr. Fleming with naturalist/guide Alanzo (pictured right), Quetzal showing

farmer William (left) and Serrano family member (far left); photo

taken by James Regali, Bob’s companion on the Quetzal search.

|

This week’s blog piece and photos make up the third installment in our Musings of a Naturalist series, courtesy of our own Dr. Robert (Bob) Fleming: Professor Equity and Empowerment/ Natural History. Having grown up in the foothills of the Himalayas in India, Bob has long been interested in the beauty of nature. This progressed into a fascination with natural history and cultural diversity, leading him to obtain his Ph.D. in zoology. He has explored many of the planet’s special biological regions, ranging from the Namib Desert in Africa to the Tropical Rainforest of the Amazon, and the Mountain Tundra biome of the Himalayas. He has worked for the Smithsonian’s Office of Ecology and the Royal Nepal Academy and, along with his father and Royal Nepal Academy Director-Lain Singh Bangdel, he wrote and illustrated “Birds of Nepal,” the first modern field guide to the birds of the region. In addition to his work with Future Generations, Bob is the director of Nature Himalayas, a sole proprietorship that he began in 1970. Through this company, Bob has led some 250 outings. He currently lives in the temperate rainforest of western Oregon in the USA’s Pacific Northwest.

Many thanks to Dr. Fleming for another great contribution!